Witty, Sexy, Gimmicky British Pop Art

Witty, Sexy, Gimmicky British Pop Art

While the term Pop Art is widely known nowadays, its artistic scope and the issues it raises are nonetheless frequently misunderstood. Pop Art in Britain refers to a group of artists who began appearing on the scene in the mid-1950s. This identity was formed around The Independent Group – an intellectual circle consisting of the painters Eduardo Paolozzi and Richard Hamilton, the architectural partnership of Alison and Peter Smithson, and the art critic Lawrence Alloway. In its theoretical explorations, The Independent Group focused on a speculative exploration of technology, hence the recurring references to science-fiction in British Pop Art.

Daily life in Britain was drab and grey for some years after the War. Rationing of food came to an end only in 1952, and the benefits of the Capitalist system enjoyed by Americans – abundant consumer goods, television, increased leisure time – only gradually began to become reality for the British in the early 1960s. When Prime Minister Harold Macmillan proclaimed in 1957 that ‘You’ve never had it so good’, it was still for many a case of wishful thinking. British Pop Art, particularly in the forms that emerged in the work of painters studying together at the Royal College of Art in London during the early 1960s, was largely the invention of working-class men whose early years coincided with the deprivations of World War II. It was perhaps this common experience, rather than pure serendipity, that explains why the intake of students in autumn 1959 included so many who were to become important figures in the movement by the time they completed their postgraduate course three years later. David Hockney and Allen Jones, both born in 1937, and the American R. B. Kitaj, born in 1932, who had settled in England in 1957 and was studying there under the terms of the GI Bill. Patrick Caulfield, born in 1936, arrived at the College in 1960. Earlier in the 1950s other British artists had paved the way. Two prominent members of the Independent Group, Richard Hamilton and Eduardo Paolozzi, had put into practice many of the group’s conjectural interests in product design, advertising, science fiction and the cinema. The word pop itself had first been used in a fine art context at their meetings, and its first published appearance in this sense was in a 1958 article by Lawrence Alloway, one of the critics at the heart of the group. Much of the material to which Hamilton and Paolozzi had recourse was American in origin, in particular the glossy magazines which they plundered for collage material and which they used as a repository of exotic, alluring images of a prosperous way of life.

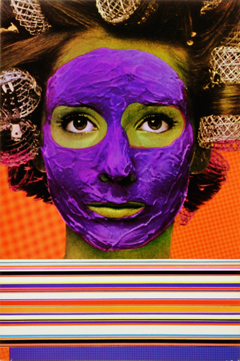

Aside from their genealogical divergences, British Pop Art and American Pop Art occupy common ground in their assumption of the same term. The term Pop Art, coined by Alloway in the late 1950s, indicated that art had a basis in the popular culture of its day and takes from it a faith in the power of images. But while Pop Art quotes from a culture specific to the consumer society, it does so in an ironic mode, as inferred from the British painter Richard Hamilton’s definition of his artistic output: “Popular, transient, expendable, low-cost, mass-produced, young, witty, sexy, gimmicky, glamorous, and Big Business”.

Everyday life was an endless resource for the pop artist. Pop stresses frontal presentation and flatness of unmodulated and unmixed color bound by hard edges. It suggested the depersonalized processes of mass production. Pop Art investigated areas of popular taste and kitsch previously considered outside the limits of fine art. It rejected the attributes associated with art as an expression of personality. Works were close enough to reality yet at the same time it was clear that they were no ready-mades but artificial re-creations of real things. Pop Art definitely broke the hegemony of Abstract Expressionism in Europe and the United States that occupied center art stage in 1950’s-1960. It excreted the edges between high and low art. Pop Art confronted institutional art with everyday endless objects which gained, when displayed as art, a new quality.

General Dynamic F.U.N., 1970

Screen print on paper